Stuart Preston

Commentary

(a perceptive view from a Master “Art Critic”)

Weighed down by the burden of its long and magnificent past modern Italian painting was a late starter on the avant-garde front, breaking out in other European countries in the early years of the century. For an Italian artist, cutting loose from tradition was no simple matter. His had been a violent separation in order to be an effective one. His had to be a violent separation in order to be an effective one.. And violent it was indeed when, on the eve of World War 1, the Futurists threw tradition to the wind with such determination and gusto. Their declaration of independence rang round the world. Not the least of its subsequent benefits was to have given later generations of Italian artists the freedom to join the mainstream of modern art, each in his own way

|

The Italian painter, Nicola Simbari, who has won worldwide renown since coming to artistic maturity, in about 1950, is outstanding among his contemporaries. In that he is a semi-abstract expressionist, we can recognize his affinities with other avant-garde artists, both in Europe and America. What distinguishes his work, as generically Italian, is a notable exuberant energy, a characteristic of the Italian artistic temperament from the Renaissance onward. More specific reasons for the appeal of his art to connoisseurs and collectors alike, are the facts that, for Simbari, painting is another word for feeling, and that brilliant colour is a means of dramatic expression rather than being decorative for it own sake. What a relief to find on the International Scene, an artist who has something to say and the ability to say it clearly, in his own language.

Born in Calabria, in 1927, and brought up in Rome, where his father worked as an architect (builder) for the Vatican, Nicola Simbari took up painting seriously on being demobilized from the Army at the end of the war. He first studied at the Accademie delle Belle Arti, in Rome, and then branched out on his own, taking, in 1949, a studio in Via del Babuino, and, then holding his first One-man Show in Rome in 1953. Since that time his fame and success have extended far beyond the boundaries of Italy. Throughout Europe and in the United States he is recognized, today, as a key figure in Modern Art.

Like most artists of his generation, on the International Scene, Simbari was influenced by Abstraction, which enjoyed its heyday during the early 1950s. However, temperamentally, he held back from extremes of abstraction, not so much because he found them unrewarding, dull or meaningless, but for the reason that a totally dehumanized Art is alien to his nature. For the true Artist, his work is inevitably an extension of personality, and Simbari has no other course to follow, but his own. Motivated, more by interest in humanity, and in his daily life, than by theory, he has, at his command a wonderful prodigality. And - - a natural way of expressing, and communicating, simple basic feelings, with a complete absence of rhetoric or sentimentality. In their subtle and indirect ways, his paintings of landscapes and figures are recognizable as such, but he is too excited by purely pictorial problems - - design, colour, technique - - to allow for any lapse into the anecdote.

|

Various Etchings ©Nicola Simbari |

|

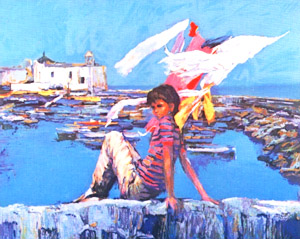

Of paramount importance to Simbari is conveying his feelings about a given scene in all their original intensity. He is neither an intellectual artist nor a theoretician. As with all painters of this temperament, he sometimes falls short of communicating the maximum response to what catches his eye. On such occasions, I would be inclined to blame the subject rather than the artist. Romantic feeling cannot be turned on like a tap, and Simbari reacts best to scenes in the actual visible world, which most keenly engage his mind and heart. First among these, are glimpses of the Mediterranean seashore, where figures, often caught unawares, wander along the beaches, and where everyday life is lived in ‘public’. Naturally enough, Italy is the country to which he is most profoundly attuned. Not that he is in any sense a topographical artist, or a literal reproducer of what attracts his eye. For him, visual facts are apt to become symbols of themselves. Rocks and the sea represent the timeless elements of nature, while figures stand for certain human moods, whether of gaiety, sadness or just ordinary perplexity. Simbari is both more and less than a realist. It matters very little whether this or that beach scene, depicts the Roman coastal area: Sicily or Calabria. What is far more important to him (and, consequently, to us) is their power to evoke the peculiar character of Italy.

In fact it helps a great deal in the appreciation of his work to have some acquaintance with these regions, for Simbari’s interpretation of them is actually more faithful to visual facts and less stylized than we might at first imagine.

Certainly, we know more about Cezanne, after visiting Provence, or about Monet from familiarity with the Valley of the Seine. However oblique and fanciful Simbari’s rendering of a given scene may be - - and he can take extreme liberties with it - - he is most true to himself when dealing with what he knows best. For this reason, Italian subjects are, in my opinion, his best work. Familiarity breeds understanding, and having one’s roots in the soil (as opposed to one’s feet on the pavement`) provokes more profound responses and brings closer together the visible and suggestive elements of a landscape. Simabri’s esthetic interest, lies chiefly, in the world about him. He is primarily an enjoyer of what he sees - - of people sitting in a café; or strolling up and down the street; or simply existing for the moment, or immemorially in time.

| . . . hosting, friends at “home” away from the easel !! Click picture for detail. |

“When I am painting,” he has said, “ I’m like a writer. I must have something to say. My paintings are like entries in a Diary; they are my reactions to all the things I’ve seen . . . I want people to understand visually what I’ve done. A rock must look like a rock” Such a genial approach to the visual world counts for very much in the wide appeal of his work. His perceptions sharpen our own perceptions of the same, or similar, episodes in daily life

Now, there is a school of thought, which considers mundane visual interest as of little importance in a work of art. We are living in a catastrophic age, vast and impersonal, threatened daily by total disaster. How then, runs the argument, can an artist, say, like Simbari, afford to ignore the forces of evil abroad and just content himself with recording daily life in the sunshine? Doesn’t an ‘Action Painter’ reflect artistically, and faithfully, the anarchy of the present day? Or . . . Isn’t the purity of nonfigurative abstraction a more accurate reflection of Life’s sheer emptiness? Such arguments seem to me to be totally wrong. Granted that an Artist is as aware of present-day troubles, as the next person - - - Isn’t it still his principal function to create vivid , memorable and beautiful images?

|

“Nino” retablo in silkscreen ©Nicola Simbari |

When celebrating such values as those of the Sanctity of Human Life, what business is it of his to concern himself with Social, Political, or Military events? Artists who consciously try to reflect in their work matters of topical interest, will soon be forgotten, along with that topicality. Their attitude strikes me as being presumptuous, and even frivolous. Mercifully, it is a rare one, and, mercifully, too, the true artist celebrates Human joys and sorrows, and leaves threats of global disaster to soothsayers. For the World is represented far more faithfully in its physical beauty, and in poetic interpretations of the same, rather than in the aridity of geometric design, or the hysteria of abstract expressionism. As Simbari himself has said, “ Life is Baroque, more complicated than geometrical patterns.”

One’s first impression - - it has almost the force of a physical impact - - of a Simbari painting, is that of full-blooded colour, laid on heavily with the palette knife, in smaller or larger rectangular slabs of luscious paint. With this method he makes the picture surface vibrate with Life. Even light is transformed into colour, for colour is Simbari’s element, in which he dives and splashes, with all the abandon of a porpoise. Superficially, the effect is decorative, but when we look further into the picture, we realize that the dramatic and sumptuous paint-colour technique is the most functional element in his work. It defines space, establishes the identity of objects, and creates an entirely convincing and integrated harmony, or world, within the picture frame. Furthermore, he uses paint-colour as a means of expressing the emotion aroused in him by his subject matter, and the subject is important to him. He convinces us that, no matter how explosively he throws off great solid fragments of colour pigment, which glisten like uncut precious stones. This is, admittedly, an extravagant style, but suits his favourite subject matter - - figures and landscapes, which urgently engage our attention. In his best work, when everything comes together, the result has convincing power. What he has seen and felt is dramatically materialized.

We do not necessarily try to identify the landscape, or wonder which model has been posing for him, for Simbari’s paintings are emotional conceptions without need of more precise definition. It is a dynamic style, and yet it depends on carefully observed subject matter to justify its existence. Otherwise such a style would almost result in paint cookery, in the creation of agreeable substances. Subtle calculation in translating the subject into his own stylistic terms, underlies the tumultuous picture surface. It cannot be declared too insistently that, for Simbari, the use of paint-colour is subservient to the image, and not at all an arbitrary exercise.

|

There is a marvelous richness to this artist’s symphonic manipulation

of sumptuous colour. Impressive by its variety and constant quality, it

affects us in its own right, as matter, while simultaneously

re-creating existing forms. One’s experience of such things is renewed

and revitalized.

“La Piazzetta di Capri” oil on canvas ©Nicola Simbari |

One is reminded of Paul Klee’s observation, that nature, when being

transferred to a canvas, must be :

Klee was a very different kind of artist from Simbari. Nonetheless, this statement applies well to the latter, and formulates Simbari’s conception of the role of an Artist.

Some years ago, the fashionable avant-garde held that figurative painting was a ‘reactionary activity’, and that those few artists who practiced it were either ‘survivors from the past’ or else, just foolhardy, misguided and even eccentric. And yet, during those years, when ‘Action painting’ flooded the market place, the three modern Artists most admired were Giacometti, Dubuffet and de Kooning. All of whom never ceased wrestling with the problem of depicting the human figure. Hence, to put Simbari in the role of ‘leader’ of a new movement called “return to the figure”, is to ignore the fact that to depict human beings has never ceased being the hardest worked theme in Art. Unless he were a mere copyist, employing the worn-out clichés of earlier generations, the figurative artist has constantly to think things out afresh. This is a difficult problem, and has been bravely faced, by Simbari, in his own personal way, which reconciles three apparently disparate elements, the sensuous, the suggestive, and the rejection of the commonplace of Realism, as such.

It would be foolish, at this moment, to pass anything like a final judgment on Simbari’s role in Post-War European painting. For one thing, he has only just arrived on the threshold of middle age; for another, he possesses an immense vitality and naturally looks more to the future than the past. What direction his Art will next take, cannot be predicted with any certainty, even by himself, but one can be certain, without fear of being mistaken, that he will never become a passive spectator, contemplating the world from the top of an ivory tower. He is involved in things. He is what the French call “un peintre engage”.

Almost invariably, this is the Mediterranean scene of which he has an innate appreciation, so much so, that his transcription of it takes on something like a symbolic character. One doubts if he will ever depart from a kind of art that is based on appeal to a humane and civilized scheme of things. It is a material world which holds his passionate attention. Of this preference, one is reminded of Jean Dubuffet’s remark: “I am struck,” he said, “by the high value for a man, of simple permanent fact, like the miserable vista on which the window of his room opens daily.” It is this semi-visionary love of the visible world which distinguishes the Art of Nicola SIMBARI. He re-affirms the love of all Material things, whatever they may be.

|

“Afternoon in Procida” oil on canvas ©Nicola Simbari |

Back to the top